The Appalachian Prison Book Project operates out of an old stone house in Morgantown, West Virginia, sending free books to prisoners in six nearby states.

State prison systems have strict standards about who can mail books to incarcerated people. So books-to-prisons nonprofits work with each state to get on the list of trusted book vendors. The Appalachian Prison Book Project (APBP) has been on Tennessee’s list for years.

“We get about 200 letters a week from people incarcerated asking for books that they’d like to read,” says Lydia Welker, the group’s spokesperson. “They might ask us for a certain author or a genre or a specific title. We have our volunteers read (the letters), and then look through our shelves of donated books to try to find the best possible match.”

Sometimes a book will be rejected and returned for violating prison rules.

“Books with nudity in them,” Welker gives as an example, “even art statues like Michelangelo’s David.”

But Welker said that one day last April, something unusual started happening to the books going to Tennessee.

“We got four tote bags worth of books returned from state prisons in Tennessee that same day.”

APBP soon figured out why: The Tennessee Department of Correction, or TDOC, had taken it off the list of approved vendors. And the same thing happened to all the other books-to-prisons programs that serve the state.

The change has impacted those nonprofits and the people within Tennessee prisons, and it mirrors similar moves in other states.

Appalachian Prison Book Project

Appalachian Prison Book Project

The Appalachian Prison Book Project operates out of the Aull Center, an old stone house in Morgantown, W. Va. It sends donated books to prisoners in nearby states.

The policy change

Now, a person in prison who wants a certain book has to buy it, or get someone else to buy it, directly from the online bookseller Abebooks, or from a few other authorized sellers and publishing companies.

A spokesperson for TDOC said the change was made “to mitigate the introduction of contraband through mail” and that the rule wasn’t revised because of any specific incident.

Data from another state prison system, in Florida, showed that only around 1.7% of prison contraband came through the mail. Reporting from The Marshall Project and the Texas Tribune found the largest share of contraband in Texas prisons was brought in by guards.

TDOC’s contraband reasoning doesn’t hold up for researcher Moira Marquis, the lead writer of a Pen America report on censorship in prisons. She says one reason prison systems crack down on physical mail is viral misinformation circulating among staffs nationwide.

When they screen mail, “Corrections staff are recording each other when they think they have touched fentanyl-laced paper,” she says.

The staff members believe they’re overdosing, and they start to hyperventilate. But in a real overdose, a person usually goes catatonic and stops breathing.

“These corrections staff are recording each other, essentially, having panic attacks,” she says.

‘Almost nobody’

Kelly Brotzman directs the Prison Book Program in Quincy, Massachusetts, which serves jails and prisons in all 50 states. She says the TDOC policy change will have a huge side effect. It shrinks the number of prisoners who can access books to almost no one.

Prison Book Program

Prison Book Program

Volunteers for the Prison Book Program search for books to send to prisoners.

“You don’t have the internet as an incarcerated person,” she says. “You can’t order them. Plus you don’t have any money.”

In Tennessee, prisoner wages range from 17 cents per hour to a $1 per hour for “specialty” jobs.

“You need a loved one on the outside with both the connectivity and the disposable income to order books directly to you from one of those sources,” Brotzman says. “And that’s almost nobody in prison.”

Prison libraries often aren’t a good option either.

“Anybody that you talk to who’s inside will tell you that the number of books in a prison library is inadequate for the number of people that are there,” says Marquis, with Pen America. “The number of hours that they’re open is inadequate. The staffing is inadequate. The titles haven’t been updated in forever.”

Marquis says that many prisoners are functionally illiterate — they know the basics of reading, but struggle with reading comprehension. Research shows that, to grow as readers, functionally illiterate people need books that are relevant to their identity or interests, which prison libraries often lack. Books-to-prisons programs say they see many requests for stories with LGBTQ characters, or how-to guides for hobbies like knitting.

‘A drive I did not before possess’

Prisoners have already seen the effects of the policy change. Brian Hurst is incarcerated at the Turney Center Industrial Complex about an hour west of Nashville. He says he was getting free books from a church in Pegram that had to stop sending them because of the new rules. He also says reading in prison has changed his life.

“I learned so much about myself,” he wrote to WPLN. “I learned just how vast my interests are, how many things, places, people I am curious about. I found escape, and in that escape a newfound purpose, a drive in life I did not before possess.”

Hurst talked with other prisoners at Turney who wrote to WPLN about what the revised rule means to them. One man, Greg, who asked to use only his first name, said he and others were required by their Unit Manager to ask permission before they ordered books. He called this “a needlessly restrictive and personally demeaning policy.”

Prisoner Jamie Rouse said he was often frustrated when checking out fiction series from the prison library, only to find the concluding volumes missing.

“I have to purchase books in order to read the rest of the series,” he wrote.

Some prisoners at Turney said they wished Amazon was not banned as a source for books, because it includes a much larger selection than the permitted booksellers.

“Venders such as Amazon, Edward R. Hamilton, etc. have so many more options that we need for perusal,” wrote Damien Tolson.

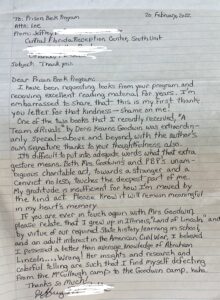

Prison Book Program

Prison Book Program

The Prison Book Program in Quincy, Mass. gets thank you notes from prisoners around the country. This one, from Florida, expresses gratitude for receiving a book on Abraham Lincoln.

(Hurst noted that Tolson “was really proud of that last word (perusal), even though some men debated his chosen usage. He even grabbed a college dictionary to try and win the debate.”)

The most common requests to books-to-prisons nonprofits are for dictionaries.

Tennessee native Lorenzo Kom’boa Ervin says there is a long tradition of prisoners reading for personal growth. When he was in federal prison in the 1970s, the only books allowed were bibles — he helped lead a lawsuit that ended that restriction. Then he started a political reading group with other prisoners.

“People who had a criminal culture, you know, had been gangsters and so forth in the street — all of a sudden they started to read and they started to understand … some of the economic and political injustices of society that led them to prison,” he says. “And it changed their focus entirely.

“Instead of the use of violence to, you know, get the things that you needed in life, it allowed people to understand that there was a new possibility.”

Some even made reading and learning their life’s work.

“There are people that I know personally that left the prison system and became academics at universities,” Ervin said.

Limited options

TDOC says there is another way books-to-prisons programs can still send books: donating them to prison libraries, rather than mailing them directly to prisoners.

But Brotzman of the Massachusetts-based program says that’s not a reliable way to get a book to a prisoner who wants to read it.

“Just because your facility has a library doesn’t mean you have permission to go to it. It is a privilege that can be taken away and is very frequently taken away,” she says. “(And) there’s no guarantee that that book would not go missing when mailed to the library. It happens all the time. Someone swipes the book, steals the book.”

Brotzman says Tennessee isn’t the only state that books-to-prisons nonprofits are having trouble with. Arkansas and Missouri have adopted similar policies. A lawsuit is in the works in Missouri, but books-to-prisons groups are often reluctant to sign on as plaintiffs because they fear retaliation from prison systems.

For now, Tennessee’s policy change will remain in effect, and prisoners will have far less access to the books they want.